When we talk about “healthy living,” we usually think of food, exercise, sleep, maybe stress.

Almost nobody says: “I’m working on my lighting.”

Yet, as neuroscientist Professor Glen Jeffery argues in a recent Nature paper and in conversation with host Dave Wallace on the latest episode of Sunlight Matters, the light we live and work under – especially harsh, narrow-spectrum LED lighting – may be quietly pushing our metabolism and our vision in the wrong direction.

And the fix isn’t futuristic. It’s… old-school light bulbs and a bit more sunshine.

The experiment: real people, real office, really bad light

Instead of doing a tightly controlled lab study with volunteers sitting in front of a special lamp, Jeffery’s team went somewhere much more familiar: a grim, windowless part of a University College London building.

No natural daylight

No meaningful view of the sky

Lit entirely by harsh white LEDs

People working there all day, especially in winter, often barely seeing daylight

In other words, a worst-case version of the modern workplace.

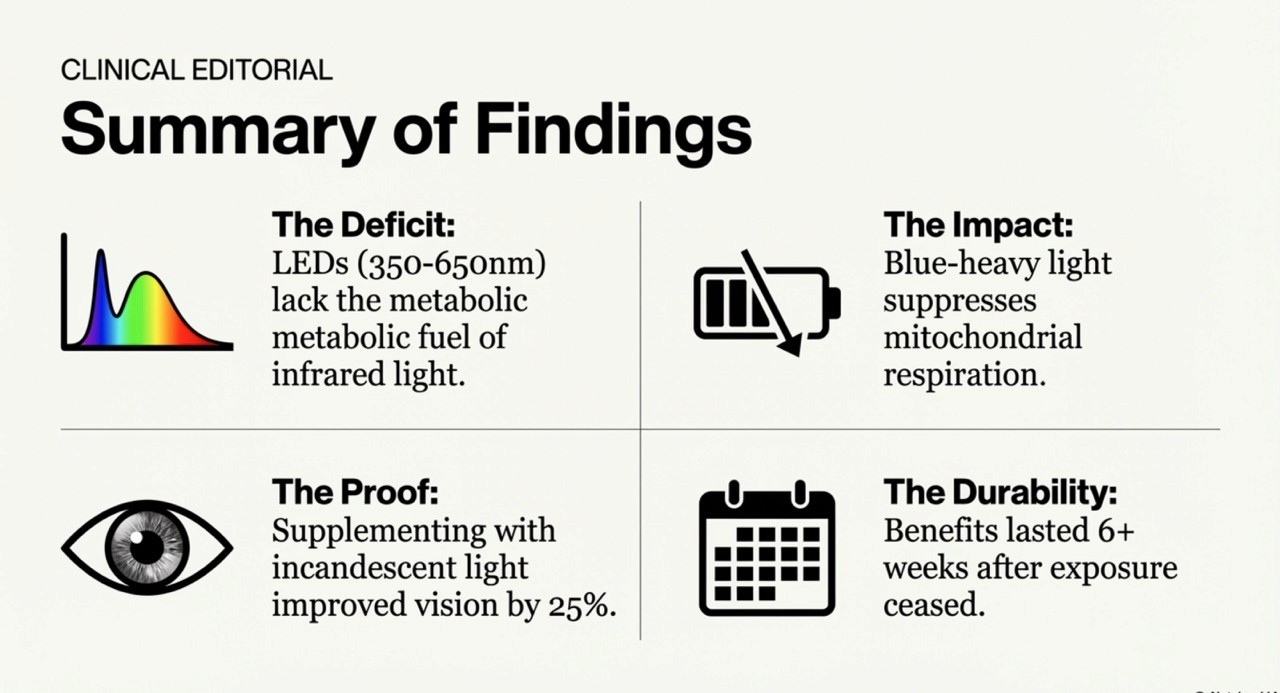

They chose vision as their main metric because it’s easy to test in a repeatable, “hard science” way: you can measure how well people see color or contrast today, and then again tomorrow, and compare numbers.

Here’s what they did:

Baseline testing – They measured workers’ color vision in that LED-lit basement. On paper, it seemed “fine.”

A simple intervention – They placed old-style incandescent bulbs on people’s desks and around the space.

No one was told to stare into them.

The LEDs stayed on.

The instructions were basically: just live your normal life, walk around them, go to the bathroom, eat lunch – let them be part of your world.

Re-test – After people had been living with those incandescent bulbs in their environment, the researchers measured color vision again.

The result? A highly significant improvement in vision.

Simply adding warm, broad-spectrum incandescent light into a harsh LED environment improved visual function measurably.

Then they removed the bulbs and kept testing.

The improvements lasted for weeks, approaching a couple of months – right up until the study had to stop for Christmas, when everyone’s environment and habits changed.

That lingering benefit stunned the researchers. Something in the biology had been restored, not just “boosted for a moment.”

Why LEDs are a problem – and incandescents behave more like sunlight

Most modern LEDs share the same hidden problem:

They only give off the part of light we can see.

Sunlight – and old incandescent bulbs – are totally different. They produce light via heat, which naturally creates a broad spectrum that includes not just visible light, but also a lot of long-wavelength infrared.

You don’t see this infrared, but your cells do. Jeffery and colleagues (and physicists like Bob Fosbury) point to mitochondria, the tiny power stations in your cells, as the key players:

Certain wavelengths of long-wave red and infrared light improve mitochondrial energy production.

The wrong light environment – heavy on LEDs, low on infrared – appears to suppress energy production, disturb metabolism, and degrade visual performance over time.

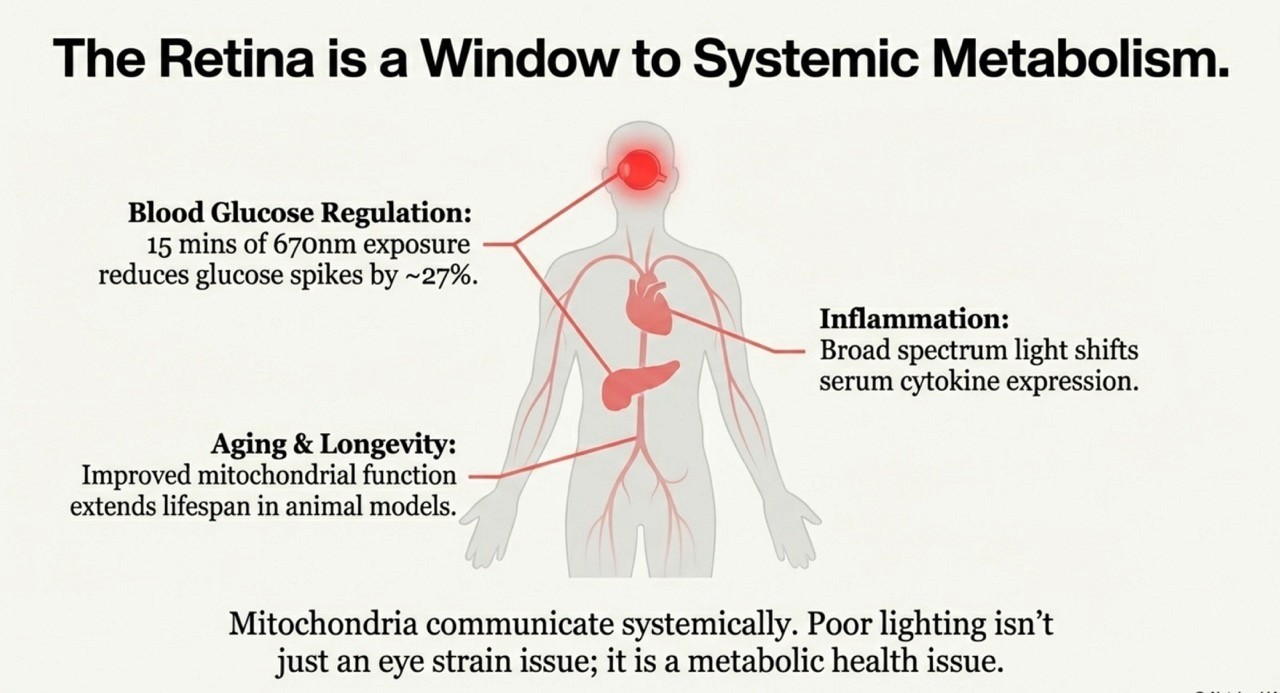

In animal experiments, when animals are kept under LED lighting and then given specific long-wave light exposure, their:

Blood sugars improve

Lifespan and healthspan increase

Flip that around, and you get the uncomfortable statement Jeffery makes in the conversation:

LED lighting, in the way we currently use it, is suppressing metabolism and pushing us toward a pre-diabetic state.

In humans, this seems to play out as:

Subtle but measurable impairment of color vision

Shifts in blood glucose regulation

Likely effects on overall metabolic health that we’re only just starting to understand

So incandescent bulbs end up being more than nostalgic. Spectrally, they’re surprisingly close to daylight, full of the “invisible” wavelengths that our biology evolved with for millions of years.

Glass is part of the problem too

Even when we do get “natural light” indoors, much of it is filtered through modern glazing that blocks infrared.

In the building Jeffery studied, what little glass existed blocked almost all non-visible light. So even if you thought you were near a window, your mitochondria were still in the dark.

This has huge implications for:

Architecture and urban planning – We talk a lot about daylighting, but often only in visual terms: Is it bright enough to read?

We now need to think in terms of full-spectrum solar exposure, not just lux levels.Real estate and home buying – “South-facing, lots of natural light” may not be enough if the glass blocks the wavelengths that actually support metabolic health. Smart buyers and developers will increasingly want sunlight analysis, shadow mapping, and real estate sun studies that consider spectrum, not just brightness.

Hospitals and care homes – Many new buildings use infrared-blocking glass and are lit entirely by LEDs, especially in operating theaters and intensive care units.

Those design choices might be saving energy and cooling costs – but at what price to recovery, healthspan, and public health budgets?

The big-picture health and economic stakes

Jeffery emphasizes that what looks like a small technical detail – the spectrum of indoor light – could have massive public health consequences.

Some examples he mentions:

1. Diabetes and metabolic disease

Animal data show LED-like spectra can drive animals into a pre-diabetic state.

Human data are lining up in the same direction.

The cost to health systems like the NHS of diabetes and related complications is enormous and rising.

In some regions (e.g., Gulf states), diabetes rates are astonishingly high, and people spend much of their lives:

Indoors

Under LED lights

Behind infrared-blocking glass

Often with ultra-processed diets layered on top

Contrast that with traditional communities living mostly outdoors under natural light – such as those in parts of Papua New Guinea – where diets can be high in carbohydrates, yet diabetes remains rare.

Light exposure is a plausible missing piece in that puzzle.

2. Hospitals and “bed blocking”

For decades, nurses and doctors noticed that:

Patients by the window get out of bed earlier.

Better light exposure seems to improve mood, mobility, and recovery – even if people didn’t know the mechanisms. Now we’re learning that full-spectrum light and infrared may improve cellular energy and help the body heal faster.

Keeping someone in intensive care for just 24 hours costs thousands. If better light shortens hospital stays, it’s hard to argue that saving a few pennies on bulbs or glass coatings is “cost effective.”

3. Older adults in care homes

Animal studies show that older, frail animals move better and maintain better function when given the right light spectra. Now imagine:

Older adults in care homes

Low mobility, high fall risk

Poor metabolic health and blood sugar control

Living under harsh LEDs, with little direct access to sunlight

Jeffery is blunt: we’re ignoring a simple, low-cost intervention that could meaningfully improve quality of life – and potentially reduce falls, fractures, and complications like pneumonia.

A single incandescent desk lamp might do more than another expensive supplement.

What about red-light panels and IR face masks?

If you’ve been on the internet lately, you’ve probably seen ads for:

Full-body red/infrared panels

LED masks for skin and “anti-aging”

High-priced “photobiomodulation” devices

Jeffery’s view is cautious:

Many devices are wildly overpriced for the parts they contain.

Most put out far too much light – a huge wall of intense energy that the body is not evolved to receive.

In the lab, effects often disappear with overexposure, suggesting the mitochondrial system can get overloaded.

His concern is simple:

What happens to someone who uses a high-energy IR face mask heavily, week after week, for years? We don’t know yet – and that’s not a comforting answer.

By contrast, a dimmer, broader-spectrum source – like a simple incandescent bulb run through a dimmer switch – delivers much more natural exposure. Turn the visible brightness down and you still get plenty of infrared without blasting your cells.

So what can you actually do?

Until policymakers, building standards, and the lighting industry catch up, there’s a lot individuals, architects, and planners can already do.

For everyday people

Get real sunlight early and often

Morning light, especially, helps your circadian rhythm, mood, and metabolic regulation.

Even a short walk is powerful – think of it as free solar exposure therapy.

Add an incandescent or halogen lamp where you spend time

A small desk lamp or anglepoise with an old-style bulb can “buffer” the negative effects of overhead LEDs.

Use a dimmer switch: lower brightness, keep the infrared.

Reduce LED-only environments, especially in winter

If you work in a windowless LED cave, find ways to:

Take breaks outdoors

Work near a window that lets in real sunlight (if the glass isn’t heavily IR-blocking)

Add a broad-spectrum light source to your space

Be skeptical of high-powered red-light gadgets

More light isn’t always better.

Gentle, regular exposure to natural or incandescent light is likely safer and more “evolution-compatible” than intense daily blasts.

For architects, planners, and developers

This is where sunlight analysis, shadow mapping, and real estate sun studies stop being just nice sustainability extras and start becoming core health design tools:

Prioritize building layouts that maximize direct solar exposure for key spaces: bedrooms, living rooms, recovery rooms, care-home lounges.

Choose glazing that preserves beneficial infrared, not just visible light.

Design lighting schemes that mix efficient LEDs with:

Warm, broad-spectrum sources

Thoughtful placement of incandescent/halogen fixtures where people spend long hours

In critical environments – operating theaters, recovery rooms, ICUs, care homes – consider the metabolic impact of light as seriously as air quality or temperature.

And if you’re selling or buying homes, the “best home orientation for natural light” increasingly means:

Not just south-facing and “bright,” but full-spectrum daylight reaching inside for a meaningful part of the day.

The next phase of research – and why we shouldn’t wait

Jeffery’s group is now probing questions like:

How quickly can incandescent light improve vision? (Current data suggest changes within an hour are possible.)

What minimal “dose” of the right light spectrum is enough to support metabolism during critical times – for example, after surgery in recovery rooms?

But his message is clear:

We already know enough to act.

Just like with smoking, asbestos, and scurvy, the science often arrives long before policy or public perception catch up. The uncomfortable pattern is:

A technology is adopted because it’s cheap, convenient, or efficient.

Early warning signs are ignored.

Health consequences show up years later.

Eventually, standards change – after a lot of avoidable suffering.

We’re still early in the LED era. That doesn’t mean there’s no problem. It means we have a chance to change course before the full cost lands.

Reconnecting with our real light source

At the heart of this conversation is something very simple:

We are children of the Sun.

Our biology was built under broad-spectrum daylight, dancing with shifting wavelengths from dawn to dusk, warmed by firelight at night. Swapping that for narrow-spectrum LEDs and IR-blocking glass was never going to be free.

The good news? We don’t need to abandon modern life or rip out every LED. We just need to re-balance the spectrum:

More time outside.

More true full-spectrum light inside.

Smarter building and lighting design that respects the body’s relationship with sunlight.

If that means putting a “dumb” incandescent lamp on your desk in a very “smart” building – honestly, that’s a pretty small rebellion.

And your mitochondria will probably thank you.